The United States faces a staggering demographic challenge over the next two decades. Every state in the union faces this problem, and some have it harder than others. Florida faces one of the larger challenges in that the population of both young and old will be vastly increasing at the same time. This challenge will require fundamental rethinking of the social welfare state, including but not limited to K-12, higher education, pensions and health care.

The United States faces a staggering demographic challenge over the next two decades. Every state in the union faces this problem, and some have it harder than others. Florida faces one of the larger challenges in that the population of both young and old will be vastly increasing at the same time. This challenge will require fundamental rethinking of the social welfare state, including but not limited to K-12, higher education, pensions and health care.

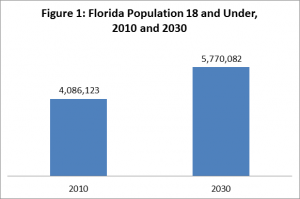

The U.S. Census Bureau projects a substantial increase in the school-aged population in Florida (see Figure 1).

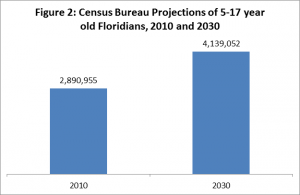

Of course, not all children under age 18 will be attending school in 2030 – most notably the children born in 2027 to 2030. So for a more precise measure of the school-aged population likely to be attending public school in 2030, we can consult a different set of Census estimates. This alternate data provides estimates on the population of 5- to 17-year-olds (see Figure 2). This substantially understates the likely size of Florida’s 2030 K-12 population, as it does not include 18-year-olds. The reader should also note the fact that 4-year-olds are eligible to receive public assistance for Voluntary Pre-K. Nevertheless, the same overall trend reveals itself: the Florida public school population is set to expand substantially.

Florida, in short, will need to find a way to educate far more than one million additional students each year by 2030. Note that Florida’s charter school law passed in 1996. The time between 1996 and now is the same at the amount of time between now and 2030. Charter schools educated 203,000 students in 2012-13.

The Step Up for Students and McKay programs educate another 86,000. It will take a very substantial improvement in Florida choice programs simply to get them to absorb a substantial minority of the increase in student population on the way. Otherwise, Florida districts will either find themselves overwhelmed with expensive construction projects, or can start using their facilities in early and late shifts, or both.

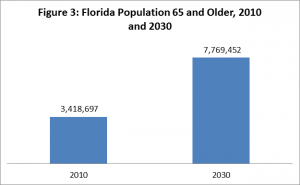

A giant new investment in school facilities will prove incredibly difficult because of the other meta-trend in Florida’s demographics: aging. The expansion of Florida’s youth population, while substantial, pales in comparison to that of the elderly population. Florida’s population aged 65 and older projects to more than double between 2010 and 2030, from approximately 3.4 million to almost 7.8 million (see Figure 3).

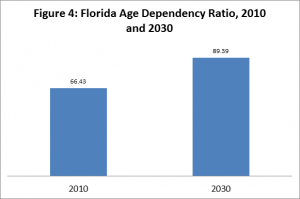

First let’s answer the question, “Why is this a problem?” Economists and demographers calculate “age dependency ratios” as a measure of societal strain. The calculation is simple – you add the number of young people to the number of older people, and then divide that figure by the number of working-age people. Just to tidy things up, you multiply the figure by 100 to turn it into a number rather than a fraction.

Why would you do such a thing? Young and older people utilize public services for education and health care, while working-age people carry the primary burden of financing such services at any given time. While younger and older people tend to consume state services, they tend to pay little in the way of taxes – one group having not entered the work force and the other having passed their peak earning years. People of course change from being net beneficiaries of such services to net payers to net beneficiaries over time. The dependency ratio serves as a measure of strain on the working-age population at any given time.

It is of course a mistake to classify everyone over the age of 65 as “dependent.” There are people working well into their retirement age whom none of us would trade for an army of 23-year-olds. It is likewise a mistake to think of anyone over the age of 19 as either working or a net contributor to society (yes, higher education, I am looking straight at you and your six-year undergraduate degrees and high dropout rates).

Broadly speaking however, economists have found dependency ratios to be predictive of economic growth. When ratios are high, you have a high percentage of people out of the work force and a relatively small percentage of people trying to cover the costs of their education, retirement and health care. Under such circumstances, economic growth tends to slow. Slower economic growth means fewer jobs materialize for those working-age people bearing the primary burden of maintaining the social welfare state through their taxes.

Florida, a retirement destination with a large youth population, had one of the nation’s highest age dependency ratios in 2010 at 66. Florida’s age dependency ratio in 2030, however, will almost reach 90 (see Figure 4). Painting with a broad brush, this will mean approximately 90 people riding in the cart for every 100 people pushing the cart with their taxes on an age basis alone.

Finally, we must address the level of preparation provided to the next generation of Floridians. Let’s start by noting the level of academic progress in Florida has been admirable since the 1999 reforms – NAEP scores and Advanced Placement rates are up, dropouts and college remediation rates down. Reactionaries fought the reforms that produced these gains every step of the way, and some are misguided enough to continue to do so to this day.

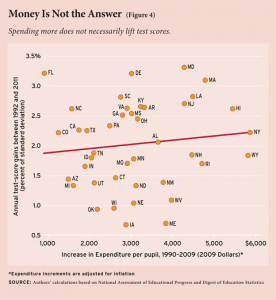

Scholars from Harvard, Stanford and the University of Munich recently demonstrated that over roughly the past two decades, Florida had the smallest overall increase in per student K-12 spending (see “Money Is Not the Answer” chart) but the second-to-largest aggregate NAEP gains. This puts Florida far ahead of most states in improving the effectiveness of the K-12 system.

And yet, here’s the sobering reality: what has been done thus far is still entirely inadequate.

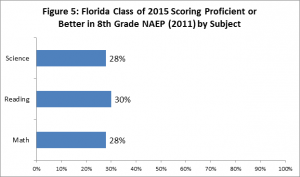

The Florida Class of 2015 will be in their prime earning years by 2030, precisely the generation charged with dealing with the expenses of a simultaneously young and old population. The Class of 2015 also happened to be 8th-graders in 2011, and took the NAEP exam. The NAEP does not provide state-level breakouts of 12th-grade scores, but Figure 5 shows us the percentage scoring “Proficient or Better” when they were 8th-graders (the last read we have on these students in the NAEP data).

Despite the fact that Florida doubled the national gain on math and reading among 8th-grade students, only a bit over a quarter of students came in with fully grade-level proficient knowledge on NAEP. The remainder of students either displayed partial mastery of grade level knowledge and skills, or fell “below basic.”

NAEP has set the proficiency bar high. Rest assured that those who surpass it will be academically prepared to face the challenges of the future. But if there is anything for you to draw from this post, it is this: the future is setting a very high bar for Florida to surmount as well. Simply put, the status quo is not an option in any of our major policy areas – K-12, higher education, public pensions or health care.

The future will be won by those capable of not only changing the world, but also able to change themselves over time in the form of frequent retraining. Future generations will not only face these enormous demographic issues, but will live in a world of unprecedented upheaval in the workplace in the face of overseas competition and the replacement of labor with technology. Each child carries the potential to change the world in a positive way and we are going to need as many innovators as we can get.

It’s not cruel to aspire to have every child reach full grade-level proficiency – quite the contrary. In the long run, it is incredibly cruel to aspire to anything else.

Americans have risen to great challenges in the past, including the defeat of fascism and communism. We face a different task in reshaping the social welfare state in such a way that it will be both more effective and more cost effective.

I don’t have all the answers, and neither does anyone else. In this case, however, even from the other side of the country, I can easily spot a conversation that urgently needs to take place.

Florida is not ready for the future.

[…] United States faces a staggering demographic challenge over the next two decades,” writes Matthew Ladner on […]

[…] other words, our education system needs to become more effective and financially efficient, fast. Large-scale school choice programs promise to do […]